We plan to fail by failing to plan

Throughout my career, I have spoken with clients and students about the benefits of preplanning activities in construction. It’s an interesting topic because I think many people, both in and out of the industry, assume that construction activities are always well planned, assuming that when something goes wrong its in the execution, not the planning. In actuality, my experience is exactly the opposite. Yes, we do plan on a macro level, spending a great deal of time on documents such as the master schedule, the construction drawings, and the project specifications. All of these things outline the plan on a broad scale, but none of them address the need to plan at a task level, which is where things generally go wrong.

At the task level, an industry trend towards Pull Planning aims to be one approach to solving our planning failures. To some degree, this does work. It focuses down another level to planning between the trades to reach one of the milestones on the master schedule. Executed correctly, this type of planning can be very effective and can help to remove constraints that have a negative impact on productivity and throughput on the job. However, it still doesn’t address planning at the individual task level.

This is the advanced planning that needs to be addressed individually, by each trade contractor, in order to ensure success out at the job site. Far too often this planning is left up to each crew, who is given little advanced notice of the specifics surrounding the task are being sent to complete. The result is that there is simply no task specific plan. They arrive on site and go at it using whatever tools and equipment they have immediately available. The failure isn’t in the execution. They are destined to fail due to a lack of planning.

How do we plan for site specific conditions that are constantly changing?

When we talk about construction, we are really talking about many different trades and tasks, all grouped together under conditions that are unique to each site. The order and circumstances under which these conditions are presented can and will vary from project to project and day to day. So how do we plan for that? Like I said, it really depends on your trade and task, but there is one constant that I have seen that is generally stays true across the construction industry. That is, we have a tendency to take the position that due to the inconsistent and ever changing nature of the industry, figuring it all out once we get there is just the best we can do.

I hear this constantly, it’s describes perfectly why our industry lacks in safety, quality, and productivity, and it is absolutely not true.

Giving in and just letting the crews wing it in the field is a recipe for failure. We may not be able to preplan and make every decision that needs to be made in advance, but we can preplan portions of the tasks that we do as part of our trade. It comes back to my earlier newsletter of complicated versus complex. Advance planning of our work in the field is both complicated and complex, and trying to take a 100% command and control approach where we leave no decision in the hands of our front line supervisors would be a mistake. However we can plan the complicated steps for each task, and give parameters and guidelines for the complex decisions that will still need to be made in the field.

Examine 3 examples taken from the field

Preplanning vertical formwork

One of my favorite examples of a company trying to get this right is Okland Construction, a large general contractor who also self performs concrete work. Okland has some very talented and highly trained craft people. They know what they are doing, and they are good at it. Consequently, they end up doing many different types of concrete work, from cast in place walls and floor systems, to decorative flatwork. Let’s look at how they preplan their work on cast-in-place concrete walls.

This is a very broad description of work, as the walls could take on many heights and configurations and the site conditions will always vary with the project. For this example, I want to look at how they have sorted out the complicated from the complex with their Features of Work documents. These simple documents are diagrams and instructions on elements they are required to incorporate and follow as they build the vertical formwork. They include diagrams for things like mandatory tie off points, guard rails and work platforms that must be in place, and they tell them at what stage these elements need to be built.

The result is that I can go to any of their projects where walls are being formed and I know I will see tie off points where they need to be located. I will see guard rails and a working platform to protect the concrete placement crews and ensure they do a quality job. More importantly, each arriving crew member knows the material to build these elements will be on site when they get there, and the placement crew behind them knows they will be installed and ready for them to use. This is a result of preplanning. Yes, there are still field decisions to be made, and they are trained to do that. Yes, there are times where some unique conditions will not allow them to follow the prescribed Features of Work document, and they have specific procedures in place to handle that.

Preplanning drywall work

Let’s switch gears to residential drywall work. I was doing some inspections for a drywall contractor and was asked to go investigate an incident that resulted in an injury, reportedly form someone falling off a baker’s scaffold (narrow frame scaffold with wheels). Skipping through many of the details and circumstances, the bottom line was that the company had been in business for many years. Over the years they had acquired scaffold components from several different manufacturers and some of the components did not fit together properly. In this case the casters (wheels) came off the scaffolding causing it to tip. I also found the brakes disabled (locked open) on every caster I inspected.

The initial response was to blame the field crew. They have all been trained and it’s the crew leaders’ responsibility to ensure things like this don’t happen. Upon further inspection though, my determination was that it was really due to a lack of planning on the part of company management.

The crew leader would arrive at the company’s yard to pick up the truck, which the yard crews had loaded with the scaffolding components they needed. For example, 10 uprights, 5 platforms, 20 casters. The crew would then drive to the job site, assemble what they had been given, and get to work. In this case, many casters didn’t fit properly in the uprights, and they all had the breaks tied open with tie wire. They came that way. In the eyes of the field crew, this is what the company sent to them. It what they were expected to use, so they did.

They knew the wheels were supposed to be locked when they were on the scaffolding, but they were sent to them locked open with tie wire, or deliberately bent to the point of not being able to be engaged. And they did the best they could to mix and match parts, they just didn’t all fit. The company’s system was a plan to fail.

The yard crews, who were responsible for maintenance, kept the brakes tied open because one or two crew leaders yelled at them when they fixed the brakes, thus imposing the unsafe habit on everyone in the company without upper management even being aware. The components were just the components to them. There was no plan to make sure they matched. The fix was easy. Color code the components that go together and make sure they have matching components. Take pictures of the conditions that make the components acceptable and unacceptable for use, and make a short checklist of maintenance and inspection items for each component coming back to the yard. Now there is a plan to make the field crews successful when they arrive on the job site.

Working in the roadway

Let’s finish with work doing street improvements. This is tough work. You are in traffic, dealing with existing conditions that don’t always match the plans, and the general public that wants better roads but is not happy about you slowing up their commute. Put this work in a neighborhood in front of schools and houses and children walking home, and you would really think that companies that do this type of work must do a tremendous amount pre-planning to ensure the safety of their people and the general public.

But you would be wrong, and the unfortunate truth here is this very often simply comes down to money. This is one of those times that a company needs to have a list of those always and never rules because there are too many possibilities for incidents with catastrophic consequences. If a worker gets hit by a car, its going to be a serious injury or fatality. If you do something to injure a driver, or a pedestrian, or someone else’s property, you are facing a law suit of the type that comes with awards for pain and suffering and even punitive damages. Awards that will be decided by a jury who is rarely sympathetic to the company that caused the injury or damage. After all, the bottom line is that if you weren’t there with the road torn up, there wouldn’t have been an incident.

I recently posted about such a condition that fortunately didn’t result in injury or damage, however, given a slight change in conditions, could have easily been catastrophic. In this case the contractor instructed the ready mix truck driver to drive through the neighborhood with several dirty concrete chutes hanging from the back of the truck. They simply didn’t want to take the time to pull them off and re-hang them as they moved from one location to the next. In fact, the superintendent told me that as long as they were driving less than 5 miles, they were not required to remove the chutes. The result was that they drove (not slowly either) with 12 feet of metal chutes dangling and swinging off the back of the truck, dropping debris as they drove at speeds of about 25 mph through a neighborhood full of cars and people. He also stated that he didn’t care about any of the concrete debris falling out of the chutes because the streets were going to be repaved anyway.

Planning to Fail - Episode 2 from Jim Rogers on Vimeo.

When they got to their destination, the crew jumped out into the street working outside of barricades and unprotected from traffic as the superintendent I spoke to complained about how fast everyone was driving and how dangerous it was. When I told him he was absolutely correct and that they should use a flagger to slow down traffic and protect their people, he argued that wasn’t required. He argued that people should see the construction and just slow down, even though no reduced speed signs were posted. Although I agree people should slow down near road construction, I wouldn’t bet my life (or the lives of my co-workers) on them actually doing so.

The advanced planning here needs to consist of always and never rules. NEVER allow a concrete truck to drive on a public road with dirty chutes hanging off the back. ALWAYS use a flagger to slow down traffic and protect your crews when the streets won’t allow them to work completely inside of a lane closure or barricaded area.

Conclusions

I originally wrote the opening of this article by stating that we don’t actually plan to fail in construction, but by the time I got to my last example, I had to change that. Example #1 is a great example of planning for success. Example #2 is an example of failure to plan. Unfortunately, Example #3 is actually an example of planning to fail. Their plan was to leave 12 feet of debris filled concrete chutes on the truck as it wound through the neighborhood at 25 mph. According to their superintendent, that is their plan for moving on public roads when the two locations are less than 5 miles apart. Their plan was to simply hope traffic would slow down. They had no intent of using a flagger or even posting reduced speed signs.

Again, you can blame it on field execution, but when they are not given a plan, or even worse they are following management’s poor instructions, it becomes easy to see why construction lacks in safety, quality, and productivity. Hopefully these examples also illustrate how easy it is to change that with some deliberate effort at the management level. How much work do you see that would be executed better if it had the benefit of some advanced planning?

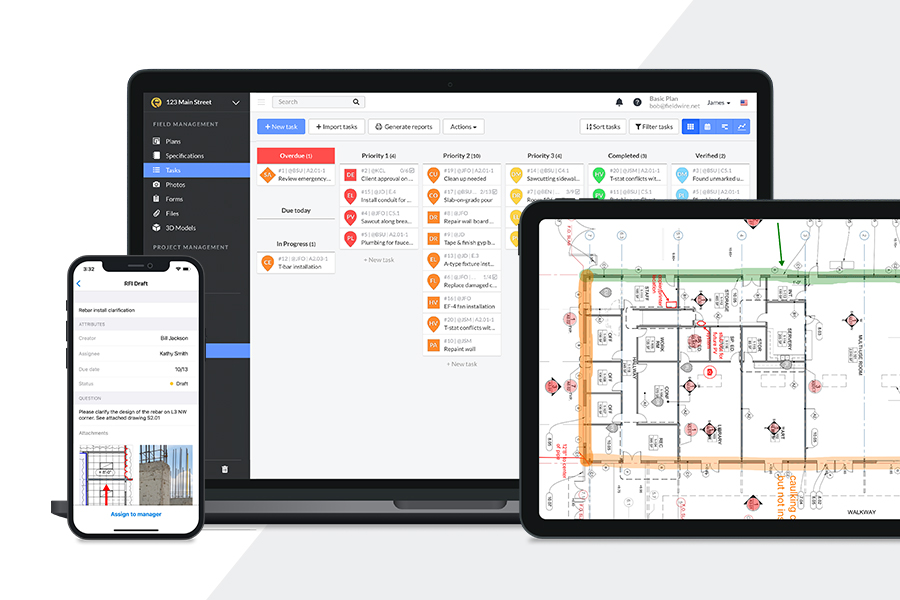

Editor’s note: Fieldwire is proud to feature construction expert Jim Rogers on our blog. Jim has decades of experience in construction management and safety, and is an instructor for LinkedIn Learning — an online library of video courses taught by industry experts from across the globe. LinkedIn Learning is a great source for construction management education and content, and it’s included if you have a LinkedIn Premium account.

Jim enjoyed learning about Fieldwire so much that he created an online course on how to use Fieldwire to manage construction drawings and processes. He then created this blog post for our readers who are eager to learn more about QA/QC processes.

Jim Rogers •

Jim Rogers •